Dorothy Day Caucus of the American Solidarity Party A Revolution of the Heart

Menu

|

What is distributism?

Distributism is a political ideal according to which property ownership should be as widely distributed as feasible. How does distributism differ from capitalism? Taken broadly, ‘capitalism’ refers to an economic system wherein property ownership is private. Its opposite is socialism, a system in which private ownership does not exist. In this sense, distributism is a political ideal that may be achieved within a capitalist system. In practice, the term ‘capitalism’ often has a more specific meaning than that above, referring to a system wherein property is concentrated in the hands of a few, and markets purportedly operate with little or no government interference. In this more restricted sense, distributism differs from capitalism, in that its policies aim at the establishment of property in more hands. Notwithstanding political mythology to the contrary, capitalism and distributism don't differ with respect to quantity of government interference: they differ with respect to its aims. In capitalism, government intervention often occurs in order to enforce the rights of the few over the many (e.g. property and patent laws), to coerce the many to work for the few (e.g. laws connecting welfare to seeking employment), and to set up the few as the caretakers of the many (e.g. laws exempting workers from liability, and requiring liability of employers). That is, capitalist use of government intervention tends towards the establishment of what Hilaire Belloc called the Servile State – an arrangement of society according to which the masses are granted a minimal level of security and care, but lack substantial wealth or political capital, and are under the mercy of those few rich persons granted legal responsibility over them in various ways. How does distributism differ from socialism? Though the term has come to have a broad range in popular discourse, ‘socialism’ strictly refers to a system in which the right to private property is abolished. Distributism is one wherein it is affirmed. The difference is that the one affirms, the other denies, a right to private property. In practice, socialist policies tend towards the establishment not of social ownership, but – like capitalism – of the Servile State. That is, they tend towards the establishment of control of property in the hands of a few, who are granted the responsibility to care for the masses at the behest of the state. So distributism differs practically from socialism in exactly the way that it differs from capitalism, because these latter tend in practice to the same thing. Is distributism a hybrid of left and right thought on economics? No. It is better to regard the left and the right as closer to each other than usually suggested. Government interference on both the left and the right tends toward the establishment of the Servile State. Distributist economic interventions aim at its abolition. One important way socialist and distributist economic regulations often differ is in that the former tend to be ‘positive’ interventions, while the latter are more often ‘negative’ interventions. Positive interventions include things like the establishment of bureaucracies to handle economic necessities for the poor, health care, college costs etc. When these exist in a mixed capitalist-socialist economy, big businesses often leverage market forces to effectively turn these subsidies into a new ‘floor’ relative to product demand, and product costs go up. In this way, positive interventions both create large managerial bureaucracies and often translate in practice into indirect subsidization of large corporations. In the absence of corresponding negative interventions, they also tend toward the ballooning of government debt. Negative interventions advocated by distributists include things like differential taxation relative to the number of stores owned or number of areas in which a ‘big-box’ company trades, the enforcement of anti-trust legislation, the taxation of ‘externalities’ like highways and pollution, and generally, various uses of taxation to directly prevent companies from serving too many sectors or too much of one sector. To the degree that negative interventions tend to involve less bureaucracy than positive interventions where the transfer of wealth must be directly managed, distributist interventions tend to be fewer, less invasive, and more efficient. Their difficulty is a purely political one: it is politically easier to advocate for subsidies than penalties, even when penalties would be of greater benefit to the class targeted for benefit than direct subsidization. How does distributism handle the distribution of goods? It doesn’t. That’s the beauty of it. In an economy where wealth is well-distributed, and the laws tend to prevent its concentration, this is accomplished by what Smith called ‘the invisible hand of the market’. In this connection, it is important to see just how often this myth of the invisible hand fails to apply in typical capitalist economies. In practice, capitalism doesn’t use markets to manage everything: prices are often set in various ways by large monopolies, in a way not substantially different than in a socialist planned economy. For instance, a large supermarket chain that owns the store fronts, the factories that make the bread sold in the stores, the trucks used to transport the product, etc. does not determine the prices of its internal transactions by the market. Likewise, fisheries dependent on having their products sold by large chains aren’t in a position to sell their goods at a better price to different stores: the price for their labor are effectively dictated to them by those who control the means of distribution. Hence, product cost in archetypical capitalist economies is often determined much more bureaucratically than capitalist rhetoric would suggest. By advocating policies that weaken and sometimes directly break up these large conglomerates, distributists allow the costs of goods to more accurately reflect their true market price, and hence to achieve the equality requisite for a genuinely free and competitive market.

0 Comments

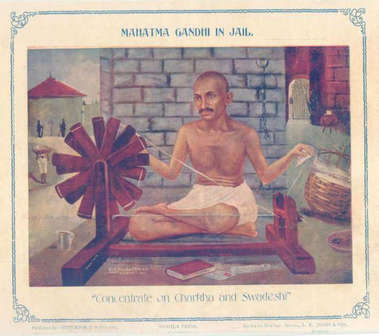

by Tara Ann Thieke  Gandhi at the charkha, symbol of the Swadeshi movement Gandhi at the charkha, symbol of the Swadeshi movement The swamps of our time do not drain; rather they spread a misery-making slime, and thus it is perhaps understandable when we accept relief or jokes when opportunity arises. There are especially easy jollies to be had poking fun at our millennial Chestertonians who have latched on to distributism, the economic philosophy du jour for political misfits. The early 20th century “prince of paradox” and most renowned distributist advocate, G.K. Chesterton, called for strikes and economic overhaul; today’s distributist dads rebel by brewing beer in the garage. Dorothy Day, the anarchist-distributist founder of the Catholic Worker houses, wanted to overthrow a rotten economic system; our crunchy conservatives have watched "Lord of the Rings" one too many times. An economic philosophy requiring total transformation of the way we live appears, in the eyes of onlookers, to be an act of self-indulgent role-playing, the inevitable result of overgrown children nursing nostalgia for a Shire which never was and never shall be. It's easy to side-eye distributism in a culture where “homemade” and "craft" are hobbies-as-accessories for the moneyed classes. The Etsy-fication of the world does little to help those without cash in pocket. What good is distributism, the principle of widespread property ownership, when agribusiness has dismantled the family farm? How could it be more than yet another variance of weekend agrarian cosplaying in an urban world where no one really knows where their shirts come from? What we need to do is smash the system. Or, we need to shore up the system with new, larger programs and plans. Or, we need to accept the system is infinitely smarter than ourselves: the dream of endless economic growth will yet deliver those still lucky to be alive in its golden dawn. Distributists are the doe-eyed children of a dreamy, dead obese man longing for illusions in a brave new future where they're too slow to keep up. They are fools to long for trees, a place to steward, land to love, skills to practice. Their loves, visions, and ideas are obsolete in the Land of Bigger, Louder, Faster, Stronger. This is the age of machines, the age of noise, and it eliminates space. It gobbles up farms. We give our children the screen as a substitute for true room to roam. Would these practical world-builders and systems-smashers raise that dismissive eyebrow at Chesterton's physical antithesis, the ascetical, piercing-eyed Mahatma Gandhi? Surely no man was less given to whimsical ramblings; Gandhi overthrew Empires without raising the barrel of a gun. After a 20th century besieged by violence of unimaginable horror, from a multitude of political systems, Gandhi's image remains imprinted on our hearts as an eternal "What-if?" Gandhi was no twee performance artist cultivating an instagram account or indulging in theoretical disputes on social media. His withered body bore the marks of his commitment to practicality, his commitment to realism; and yet Gandhi was a distributist at the same time as Mr. Chesterton, albeit across the globe. These two men sought to return independence to the people who had lost it to the same Empire. For every day and night Gandhi prayed "Swadeshi" would come to transform the Indian people, "swadeshi" meaning"local self-sufficiency,” or, the rebuilding of the home economy. Satish Kumar writes: "For Gandhi a machine civilization was no civilization. A society in which workers had to labour at a conveyor belt, in which animals were treated cruelly in factory farms, and in which economic activity necessarily lead to ecological devastation could not be conceived of as a civilization. Its citizens could only end up as neurotics, the natural world would inevitably be transformed into a desert, and its cities into concrete jungles. In other words, global industrial society, as opposed to society made up of largely autonomous communities committed to the principle of swadeshi, is unsustainable. Swadeshi for Gandhi was a sacred principle - as sacred for him as the principle of truth and nonviolence. Every morning and evening, Gandhi repeated his commitment to swadeshi in his prayers." We know Gandhi’s legacy as one of non-violence, but like that other voice of peace, Dorothy Day, his non-violence was paired with an immediate pragmatism. Gandhi looked at the sufferings and problems plaguing the villages of India and did not conclude Utopia could be established by merely evicting the British. The post-Enlightenment mindset had come to dominate the minds of his compatriots, a mindset that saw only the big and never the small, that saw theories and not faces, economic charts and not communities. This was the root of the problems. There was no free India without a free household and village, set loose from the chains of the global machinist economy the British had laid upon the Indian people. A free India meant seven hundred thousand self-sufficient villages, it meant millions of homes with their own property, their own spinning wheel, their own gardens. When Gandhi envisioned a healthy future for India he did not see a bureaucratic Leviathan, albeit run by Indians. He saw the fragile, interwoven complexity of a butterfly's wings, where each small village manifested its own strength to breathe life to the whole. The sufficiency and health of the small ensured the strength of the whole. India was not one system, one person, or one bureaucracy. Such a bloated system would never represent the interests of the people who made up India; it would only represent the interests of the system, of the nonhuman. Decades of prayer, fasting, chastity, and asceticism cleared Gandhi's eyes of the illusions and desires born of our insecurity and fear of suffering. As Gandhi’s peace and strength developed he realized how much they are the fruits of what he called “practical idealism.” Renowned for believing one must change themselves before one can change the rest of the world, that philosophy was mirrored in his economics. Swadeshi found its most successful embodiment in Gandhi's homespun movement. The home is central to the economy, and it is the home which has been displaced ever since the enclosure movement of the 1700s began to attack the English village. It is a war which has never ceased. It was enclosure which decimated the peasantry of England and drove them into the people-eating factories of the manufacturing cities. (For those interested in learning more on enclosure: Karl Polanyi’s 1944 book The Great Transformation provides one of the best histories of the movement’s underappreciated consequences; J.L. Hammond and Barbara Hammond chronicled the details in their 1917 book The Village Laborer.) It spiraled off across the planet, ever leveling homes, families, peoples, ecosystems. Today enclosure works to commodify our very bodies as companies seek patents on biological processes, or seek to microchip their employees in the name of “convenience.” An independent people are a thorn to those who would pursue their own wealth and security through dominance and possession. A world-builder cannot contend with a content neighbor. Gandhi, whose non-violence has often led him to be dismissed as a Utopian, knew the true Utopians were those who sought to build a modern Babel on the crumpled bodies and ruined homes of their neighbors. Of all the grave deeds committed by our Babel-builders, most deceptive is their audacious self-description as pragmatic realists. The geoengineers level mountains and flood valleys in their quest to claim the mantle of Heaven for Earth. From the pinnacle of the tower built on the disposable masses, they hold aloft the banner of “Free Market! Meritocracy! Endless energy! Global prosperity!” They refuse to accept their beliefs are self-imposed choices; casualties are dismissed as inevitable when they are no such thing. So a sweatshop is erected over a smashed farm in Bangladesh: “Victory is ours!” cries the Bright Young Columnist. An opioid death goes down as statistic, another victim of gun violence is carted away beneath the droning din of the city’s machinery. Their lives are nothing in comparison to the vision of the Babel builders; the technocrat’s faith in his hard-headed “realism” guards him from any potential haunting by the invisible peoples of the world. G.K. Chesterton unveiled this disconnection when he wrote: "The real argument against aristocracy is that it always means the rule of the ignorant. For the most dangerous of all forms of ignorance is ignorance of work." Our technocratic meritocracy is only a new aristocracy, and it is ignorant as to what makes for a healthy home, street, family, or world. It only knows its dreams which it dares describe as inevitable, realistic, practical. The ancient rebellion is ever with us, ever tediously the same. It is the desire to pursue our security as if it is something detached from our neighbor’s, to claim a "self" freed from reality's limitations. No claim to pragmatism can diminish the shocking, dismissive Utopianism of its goals. But is distributism any different? Is distributism simply one more attempt to dress up an individual’s scheme to refashion the world according to our desires? The virtue of distributism lies in its self-awareness, a pragmatism born of attention to reality. Novelist and philosopher Iris Murdoch noted in her work The Sovereignty of Good: “It is in the capacity to love, that is to SEE, that the liberation of the soul from fantasy consists. The freedom which is a proper human goal is the freedom from fantasy, that is the realism of compassion. What I have called fantasy, the proliferation of blinding self-centered aims and images, is itself a powerful system of energy, and most of what is often called 'will' or 'willing' belongs to this system. What counteracts the system is attention to reality inspired by, consisting of, love.” All the utilitarian, transhumanist, free market schemes have turned their attention away from reality, cloaking themselves in unearned pragmatism, and proclaiming they are truly “the end of history.” Distributism, though, is only a means, and it has enough common sense to know this of itself. Gandhi, G.K. Chesterton and Dorothy Day chose Swadeshi and distributism because it was the best way to silence the noise of the system in order to encounter the human person. It is a means, a way for us to emerge from the bombardment of advertisements or drones and hear anew, to recognize “after the fire, a still, small voice.” (1 Kings 19:12). We will not beat all our swords into plowshares tomorrow. Most of us have no reason to even know what a plowshare is, and our weapons are remote-controlled from cool, well-lit chambers. Perhaps the times force us to be cynics; Gandhi’s dream of a self-sufficient India cannot undo the great garbage patch in the Pacific. There is no turning back, we are told, so we resign ourselves to the age of noise. Dorothy Day had no time for our self-doubt which ends up benefitting the overlords of the technocracy. In one Catholic Worker edition she quoted Joseph T. Nolan: “Too long has idle talk made out of Distributism as something medieval and myopic, as if four modern popes were somehow talking nonsense when they said: the law should favor widespread ownership (Leo XIII); land is the most natural form of property (Leo XIII and Pius XII); wages should enable a man to purchase land (Leo XIII and Pius XI); the family is most perfect when rooted in its own holding (Pius XII); agriculture is the first and most important of all the arts and the tiller of the soil still represents the natural order of things willed by God (Pius XII),” (quoted in Catholic Worker, July-Aug. 1948). Surely it is of interest to us today that the teachings from multiple popes align with Gandhi’s own words: “The spinning wheel represents to me the hope of the masses. The masses lost their freedom, such as it was, with the loss of the Charkha [spinning wheel]. The Charkha supplemented the agriculture of the villagers and gave it dignity. It was the friend and the solace of the widow. It kept the villagers from idleness. For the Charkha included all the anterior and posterior industries- ginning, carding, warping, sizing, dyeing and weaving. These in their turn kept the village carpenter and the blacksmith busy. The Charkha enabled the seven hundred thousand villages to become self contained. With the exit of Charkha went the other village industries, such as the oil press. Nothing took the place of these industries. Therefore the villagers were drained of their varied occupations and their creative talent and what little wealth these bought them. “The industrialized countries of the West were exploiting other nations. India is herself an exploited country. Hence, if the villagers are to come into their own, the most natural thing that suggests itself is the revival of the Charkha and all it means,” (Harijan, 1940). The measure of a woman is not her bank account balance. Marketing fortunes are made persuading us happiness is in the goods we buy, the entertainment we take in, the fashions we pick up and discard. And if we are not entirely convinced, we will be distracted and worn down with more noise, more gadgets, more demands on the little time and energy which remains to us. The long, patient arts of making, building, participating in community, and deepening our roots do not make for good consumers. Yet without those skills or relationships we cannot have healthy homes, families, children, or land. Without taking the time to observe reality, rather than a screen, we cannot make proper judgments. There is great beauty in pragmatism, thus our eagerness to claim it. Gandhi did not describe himself as a Utopian but as a pragmatic realist. To look upon the world as it is is to see the hand of God. To look upon our neighbor as they are, untouched by our desires, wishes, or dreams, is to encounter the beloved Imago Dei. Utopianism is a denial of the goodness of Creation, for Eden began here. To encounter it anew is the task of pragmatism: to retrace our steps, this time with the heavy lessons of free will transforming our hearts into received grace. When we shed our gluttony, our lust, our need to live as immortal robots in the Matrix, then shall we hear the Good News: the Kingdom of Heaven was already within us. Perhaps some of the scorn we bestow on our bearded would-be traditionalists comes from our deep need to believe there is more to this world than a Babel which callously grinds up human beings. We are called to look upon something greater than our immediate desires, and we long for the distributists to lead us to something greater than an aesthetic purchased online. To respond to that call, we must not reject the first steps of those long cut-off from a localist, self-sufficient community. We must renew the words of Dorothy Day, G.K. Chesterton, and Gandhi in our hearts. Together, with patience, forgiveness, and steady attention to the world as it is, we may find ourselves walking into a new morning bright with the joy of our neighbors' faces. |

AuthorsTara Ann Thieke Archives

April 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed